19th Century

A Romantic vision of the landscape, enthusiasm for the art of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and the influences of Belgian, Dutch, French, and English painters informed the development of art in Munich. It reached an early high point with the so-called Leibl circle: a group of artist friends who had become acquainted in the 1860s. They were preoccupied with questions of painterly technique, which they thought was more important than the choice of motif. Besides Wilhelm Leibl himself, Carl Schuch, Johann Sperl, and Wilhelm Trübner were among the group’s prominent members.

The founding of the Munich Secession in 1892 reflected the emergence of novel tendencies, from Impressionism and Jugendstil to avant-garde conceptions of the picture. Paintings by Franz von Stuck, Lovis Corinth, Max Slevogt, Fritz von Uhde, and many others bear witness to an arts scene that nourished the artists of the Blue Rider.

From its inauguration in 1929 until the 1950s, the Lenbachhaus primarily presented paintings from nineteenth-century Munich and German art of the first half of the twentieth century. Together with the villa’s representative rooms and the art of the “prince of painters” Franz von Lenbach, these early mainstays define the collection’s historic core.

In the nineteenth century, the art of the “Munich School” was cherished by audiences and collectors throughout Germany and abroad. The local citizenry saw these works in the exhibitions of the Münchener Kunstverein, an association established in 1823 that emphasized landscapes and genre scenes. As a municipal institution, the Lenbachhaus initially focused on this predominantly private and bourgeois art, in programmatic contradistinction to the Bavarian State Picture Collections, which showcased the legacy of the Bavarian royal house, the art made at the Academy of Fine Arts, and works acquired from the International Art Exhibitions.

Learn More

Two genres are dominant — leitmotifs, one might say — in the Lenbachhaus's holdings of earlier art: portraits and landscapes. The preeminent early modern painting is Jan Polack's "Portrait of a Young Man", which was created in the 1490s. The artist’s name suggests Polish roots; around 1500, his was the most famous and busiest workshop in Munich.

In the fifteenth century, the number of portraits being produced grew as more and more princes and bourgeois clients commissioned paintings in which their faces were the central objects of attention. In Europe north of the Alps, the verism of Early Netherlandish painting, which emerged around 1430, laid the foundations for the rise of portraiture as one of the most important functions of painting. Artists now learned to capture the individual’s unique physical features as well as record the sitter’s rank and social status.

The collection includes numerous depictions of members of the nobility as well as bourgeois sitters from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Among them are works by George Desmarées, which exemplify the international style known as rococo, and Johann Georg Edlinger, the leading painter of characteristic faces in late-eighteenth-century Munich, as well as Maria Electrine von Freyberg’s delightful portrait of a child, her niece Natalie Stuntz.

In Joseph Hauber’s "Portrait of the Scheichenpflueg Family" (1811), the positions, dress, and postures of the sitters indicate that the client is a member of the wealthy upper middle class. The picture shows a moment — the father is reading a letter to his wife and children — that enables the painter to capture the individual features of the family members. The distinctness of the contours and the lively colors — in particular, the vigorous reds — recall works of French portraitists such as Jacques-Louis David. In their artless simplicity, the father and daughter embody an ideal articulated by the thinkers of the time around 1800, which was marked by profound transformations: the human being unshackled by convention.

In the portraiture of the Biedermeier, an emphatically bourgeois culture, the subjects are limned in detail-oriented and often carefully painted manner. The works in the Lenbachhaus’s collections — by Joseph Karl Stieler, Franz Sales Lochbihler, Heinrich Maria Hess, Moritz Kellerhoven, and Moritz von Schwind, among others — include conspicuously many self portraits and likenesses of artist friends.

Jan Polack, Portrait of a Young Man, 1490s

Jan Polack, Portrait of a Young Man, 1490s George Desmarées

George Desmarées

Anna Maria Countess Holnstein, around 1756 Maria Elektrine (Freifrau von) Freyberg(-Eisenberg), Portrait of a Child (Natalie Stuntz, niece of the artist), 1826

Maria Elektrine (Freifrau von) Freyberg(-Eisenberg), Portrait of a Child (Natalie Stuntz, niece of the artist), 1826 Joseph Hauber, The Scheichenpflueg Family, 1811

Joseph Hauber, The Scheichenpflueg Family, 1811

"We have the most magnificent sceneries and so thoroughly romantic landscapes in Bavaria that I am confident: the greatest artists, if they had ever seen them, would be delighted to exercise their talent here."

Lorenz Westenrieder, Bavarian Enlightenment writer and historian, 1782

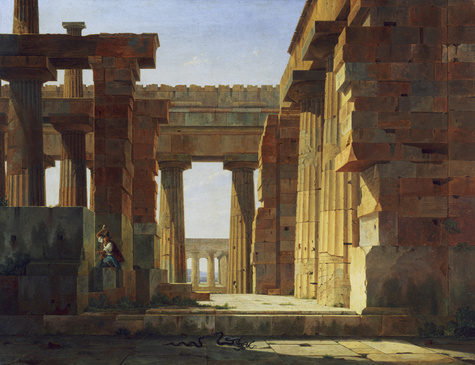

In the late eighteenth century, when Munich artists first sought to capture actual natural scenes in painting, this innovation was accompanied by the discovery of the Bavarian landscape. Influenced by the Enlightenment ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, their eyes newly open to the picturesque beauties of the pre-Alpine uplands, painters ventured out of the city and into the countryside. Instead of composing ideal landscapes emulating the examples of Claude Lorrain or Jacob van Ruisdael, they went to find their own motifs. Their audiences followed the artists: excursions into the countryside around Munich became increasingly popular.

The first generation of Munich landscape painters included Johann Georg von Dillis, Wilhelm von Kobell, Max Joseph Wagenbauer, Johannes Jakob Dorner the Younger, and Simon Warnberger. The impressions of nature they captured in sketches created en plein air ushered in a new conception of the landscape free from the constraints of academic convention. Setting colorful groups of rural or bourgeois figures in scenes beneath wide skies, painters like Wilhelm von Kobell established a distinctive style of landscape painting associated with Munich. Carl Rottmann, who was a world-famous artist in his time, Ernst Fries, and Ernst Kaiser, as well as northerners like Christian E. B. Morgenstern, Christian Ezdorf, and Thomas Fearnley followed Kobell.

Landscape painting was originally one of the disciplines taught at the Academy of Fine Arts, founded in 1808. The professorship was first held by Dillis, who was succeeded by Kobell in 1814. In 1826, the history painter Peter von Cornelius successfully advocated abolishing the chair. In the meantime, the Münchener Kunstverein, a private association of art lovers and one of the first and most important institutions of its kind in Germany, had been founded in 1823; as a counterweight to the Academy and the court’s arts policies, it now provided an important platform to the city’s landscape painters. In the 1830s, Heinrich Bürkel, who gained his renown through the association's exhibitions, shipped his landscapes, which show a life of peaceful harmony between man and his environment, to similar associations throughout Germany, becoming the author of the increasingly clichéd image that defined Upper Bavaria’s agricultural landscape in the minds of large audiences.

Ernst Kaiser

Ernst Kaiser

View of Munich from Oberföhring, 1839 Wilhelm von Kobell

Wilhelm von Kobell

On Gaisalm, 1828 Carl Rottmann

Carl Rottmann

Deer Hunting at Hintersee near Berchtesgaden, 1823 Heinrich Bürkel

Heinrich Bürkel

Th Garmisch Valley, 1839

Johann Georg von Dillis (1759 – 1841) was one of the most distinguished German artists of the period around 1800. He absorbed the traditions of classical landscape art and transformed them into a new and "realistic" landscape painting of the sort that gradually gained acceptance in the nineteenth century. As a professor of landscape painting at the Academy, arts official, and artistic advisor to three monarchs, Dillis played a major role in Munich culture; he traveled widely throughout Europe and exchanged ideas with eminent contemporaries in Rome, Florence, Milan, Paris, Vienna, and Prague.

His extensive and eminent estate, which is now held by the Historical Society of Upper Bavaria, has been on permanent loan to the Lenbachhaus since 1996. Though it includes only a handful of finished works, it comprises around 8,000 drawings and 40 sketchbooks that offer insight into the private life and creative output of the artist, who served the Bavarian court in a range of functions.

The drawings and oil sketches are the fruits of the busy art organizer’s scant leisure: Dillis rarely had the opportunity to execute oil paintings, a time-consuming process, and so oil studies, watercolors, and drawings increasingly became his media of choice. Working "in the great outdoors," he believed, was the best training for the landscape painter. Dillis thus became a pioneer of "en plein air" painting in Munich. He jotted down impressions and motifs from the world around him that fascinated him — similar in this regard to Adolph Menzel, a later artist who is reported to have said that "all drawing is good, but drawing everything is better." One important division of his oeuvre consists of the sketches he produced as he traveled. Many of them show scenes in Italy and France, but Dillis also drew incessantly in Munich and the countryside south of the city. Even outlying parts of town with their unprepossessing street corners and people drew his interest. In the last years of his life, as Dillis was increasingly unable to go on extended hikes, the view of Munich’s Prinz-Carl-Garten from his window became his most important motif. This was also where he created many of his now famous cloud studies.

Johann Georg von Dillis, Clouds with Theatine Church, 1821, Collection of Graphic Art of the Historischer Verein von Oberbayern

Johann Georg von Dillis, Clouds with Theatine Church, 1821, Collection of Graphic Art of the Historischer Verein von Oberbayern Johann Georg von Dillis, The Lech Valley with a view of the Zugspitze, ca. 1809

Johann Georg von Dillis, The Lech Valley with a view of the Zugspitze, ca. 1809 Johann Georg von Dillis, Isar with Prater Island, undated

Johann Georg von Dillis, Isar with Prater Island, undated

In 2013, the Christoph Heilmann Foundation and the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau concluded an agreement that laid the foundation for a long-term collaboration. Over a hundred works from the foundation's collection of early nineteenth-century landscape paintings have joined the museum's own holdings, a perfect complement that rounds out the Lenbachhaus's cherished collection.

Over the past years, an initial presentation in the galleries of the new Lenbachhaus offered a comprehensive survey of the collection, showcasing characteristic exemplars of the art of the Munich school and the Dresden romantics as well as the Berlin and Düsseldorf schools. The exhibition also highlighted an important subset of the foundation's holdings that is unrivaled among private collections in Germany: works of the Barbizon school of artists, who revolutionized landscape painting with the plein-air oil sketches they created in the Forest of Fontainebleau.

Gustave Courbet

Gustave Courbet

Black Rocks at the Beach of Trouville, 1865

Christoph Heilmann Stiftung Carl Rottmann

Carl Rottmann

Cosmic stormlandscape, 1849 Johan Christian Dahl

Johan Christian Dahl

Danish coast in the moonlight, 1828

Eduard Schleich the Elder (1812 – 1874), an important pioneer of en plein air painting in Germany, was an autodidact who honed his talent with nature studies he produced in the Bavarian Alps. He first met Carl Spitzweg (1808 – 1885), a pharmacist by training who similarly taught himself to paint, in the mid-1830s, when both frequented the circle of artists such as Thomas Fearnley, Heinrich Crola, and Christian E. B. Morgenstern who rejected academic convention. Together, they copied the Old Masters and roamed Bavaria and Tyrol looking for new motifs. The evolution of their art took a decisive turn in 1851, when they traveled to Paris, where they became acquainted with the Barbizon school’s paintings; they went on to visit the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations in London and encountered the work of John Constable and Richard Parkes Bonington. These discoveries led both to a new form of "intimate landscape painting" that would become a characteristic style of Munich art in the second half of the nineteenth century.

The friendship between the two artists was so close that they assisted each other in completing their pictures. It is reported, for example, that Schleich helped Spitzweg with painting his skies, while Spitzweg inserted figures into Schleich's landscapes.

In many of Spitzweg’s landscapes, the human accessories are tiny; almost the entire pictorial space is reserved for nature. What made Spitzweg famous, however, were his pictures in small formats: scenes of everyday life in the Biedermeier era, portraits of oddballs and old fogeys, romantic incidents. The "Childhood Friends" shows two unequal friends — one returning from his travels to distant lands, the other stepping over the threshold of a home he has barely left — meeting as though on a stage. As in many of his pictures, Spitzweg skillfully characterizes his figures in a style primarily associated with English and French caricaturists: lifelong monomaniacal devotion to a particular pursuit manifests itself as a deformation of the human being’s outward appearance, producing a grotesque and yet endearing original.

Eduard Schleich the Elder, Sand Pit at the Schleißheimer Allee, ca. 1860/1870

Eduard Schleich the Elder, Sand Pit at the Schleißheimer Allee, ca. 1860/1870 Carl Spitzweg, Childhood Friends, ca. 1855 or 1862/1863

Carl Spitzweg, Childhood Friends, ca. 1855 or 1862/1863 Carl Spitzweg, Papal Customs Revision, ca. 1855 or 1875/80

Carl Spitzweg, Papal Customs Revision, ca. 1855 or 1875/80 Eduard Schleich the Elder, Landscape near Munich, ca. 1860/70

Eduard Schleich the Elder, Landscape near Munich, ca. 1860/70

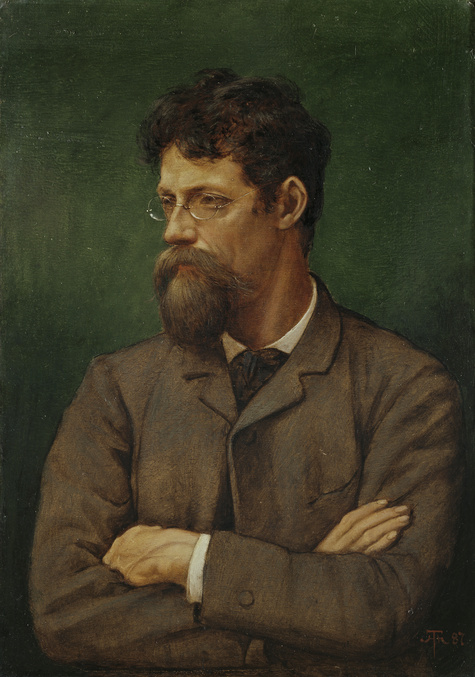

The so-called Leibl circle around the painter Wilhelm Leibl (1844 – 1900) was a loose association of artists, most of whom became friends during their time at the Munich Academy in the mid-1860s. Among its members were Wilhelm Trübner, Carl Schuch, Johann Sperl, Ludwig Eibl, Albert Lang, Theodor Alt, Fritz Schider, Rudolf Hirth du Frênes, and, briefly, Hans Thoma and Karl Haider. With the exceptions of Wilhelm Trübner and Hans Thoma, who eventually chose a very different path, these artists did not aspire to academic offices and never reached positions of privilege in society. After 1873, Leibl withdrew from the Munich art world to the countryside; with the painter Johann Sperl, he lived in Berbling and Bad Aibling, both in Upper Bavaria. Others, like Carl Schuch, spent much of their time away from Munich, in Italy, for example.

The painters of the Leibl circle emphasized the "purely painterly" register, dismissing concern with content as "literary." Another target of their opposition was the technical virtuosity prized in the Munich art world. Cool atmospheres prevail in the pictures of the Leibl circle, although dark hues often set the tone; the textures, which suggest woven fabric, result from the artists' use of broad brushes. To keep painting "honest," they worked "alla prima," applying the paint in several layers, as was conventional, but wet-on-wet, which made fixing mistakes by painting over them impossible. The collaboration between the circle's painters was closest in the early 1870, when various groups also shared studios. Then its members struck out on their own. Schuch evolved a very distinctive style in later years that was based on an exceptionally pastose application of paint. Trübner, after 1876, more than once turned to history painting, a genre the circle had roundly rejected. Leibl’s work took on aspects of Impressionism in the 1890s, a development his "Veterinarian Reindl in the Arbor" illustrates with particular clarity.

Wilhelm Leibl

Wilhelm Leibl

Veterinarian Reindl in the Arbor, ca. 1890 Wilhelm Leibl

Wilhelm Leibl

Head of a Blind Man, ca. 1866/67 Carl Schuch

Carl Schuch

Still Life with Leeks, ca. 1886/88 Wilhelm Trübner

Wilhelm Trübner

Cellar Window in Heidelberg Castle, 1871

In 1854, the "Glaspalast" or Glass Palace, an opulent exhibition hall, opened its doors, and Munich increasingly attracted artists not just from Bavaria, but from all over Germany and neighboring countries. The city beckoned with an efficient art market and a renowned academy where artists such as Carl Theodor von Piloty, Wilhelm von Diez, and Franz von Stuck taught. Most notable German artists of the second half of the nineteenth century either trained in Munich or lived here for extended periods of time. This group includes the so-called princes of painters, Franz von Lenbach and Friedrich August von Kaulbach, but also artists like Wilhelm Leibl, Wilhelm Trübner, and Hans Thoma as well as the members of the Munich Secession, among them Lovis Corinth, Max Slevogt, and Fritz von Uhde. In 1874, Carl Theodor von Piloty succeeded Wilhelm von Kaulbach as the director of the Munich Academy and became a highly influential figure. Kaulbach had represented a classicist school that emphasized the importance of delineation; Piloty, meanwhile, had spent time in Belgium and France in 1852 and studied the modern tendencies of a painterly variant of history painting that integrated elements of genre painting as well. Famous for large-format history paintings with pathos-laden theatrical scenes, he paved the way for the prevailing styles of German art in the prosperous final decades of the century. Lenbach, Franz von Defregger, Hans Makart, Wilhelm von Diez, Eduard von Grützner, Gabriel von Max, and many others were Piloty’s students. In keeping with the bourgeois roots of the Lenbachhaus’s collection, the art of Munich’s academic painters is exemplified in the museum’s holdings not by representative paintings in large formats but primarily by smaller genre and history paintings, portraits, and free studies. A particular focus in this division of the collection is the work of Gabriel von Max, an exceptional figure on the Munich scene. In 1883, when he had been professor of history painting for five years, he relinquished the position — an unprecedented step — because he wanted to devote his energies to his own painting rather than his students. Moreover, his research interests in the fields of spiritualism and Darwinism took up a steadily growing part of his time.

Carl Theodor von Piloty, Thusnelda in the triumphal procession of Germanicus, ca. 1869/70

Carl Theodor von Piloty, Thusnelda in the triumphal procession of Germanicus, ca. 1869/70 Gabriel von Max, The Vivisector, 1883

Gabriel von Max, The Vivisector, 1883

On permanent loan from the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung Franz von Defregger, The burning Seppenhaus in Reith, 1890

Franz von Defregger, The burning Seppenhaus in Reith, 1890 Hans Makart, Venedig honors Catarina Cornero, ca. 1872

Hans Makart, Venedig honors Catarina Cornero, ca. 1872

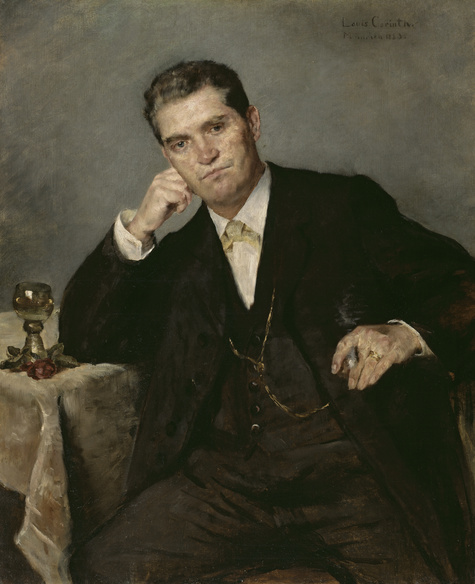

A native of East Prussia, Lovis Corinth (1858 – 1925) studied at the Munich Academy from 1876 to 1880; after honing his skills in Antwerp, Paris, Berlin, and Königsberg, he returned to the Bavarian capital. In 1892, he was a founding member of the Munich Secession. He moved to Berlin in 1900 and became president of the local Secession. In 1903, he married his student, the painter Charlotte Berend. After 1918, he spent as much time as possible in Urfeld on Lake Walchen in Upper Bavaria.

Corinth was one of the most versatile German painters around the turn of the century. The evolution of his art begins with a richly figured and almost crude Naturalism and passes through an Impressionist phase to mature into a form of Expressionism in which mythological themes recede as the portrait, the landscape, and the still life gradually become the dominant genres.

"Self Portrait with Skeleton", created in 1896, shows the artist at the age of thirty-eight. The picture is the first in a series of self portraits Corinth would usually paint on July 21, his birthday, a habit he maintained without interruption from 1900 to his death. Corinth does not present himself in the act of painting, instead turning to face the beholder with a stern and morose gaze, his body a massive physical presence. A skeleton hanging behind his back seems to look over his shoulder. A standard piece of furniture in nineteenth-century artists’ studios, it is here also an allusion to the traditional "memento mori".

Max Slevogt (1868 – 1932), the second great German Naturalist and Impressionist after Corinth, lived in Munich for most of the time between 1885 and 1897 before settling in Neukastel, Rhenish Palatinate. His "Danae" was removed from the exhibition of the Munich Secession in 1899 because the organizers feared that the realist depiction of a non-classical female body in a scene from classical mythology might cause a scandal.

Lovis Corinth, The Pianist Conrad Ansorge, 1903

Lovis Corinth, The Pianist Conrad Ansorge, 1903

On permanent loan from the Munich Secession

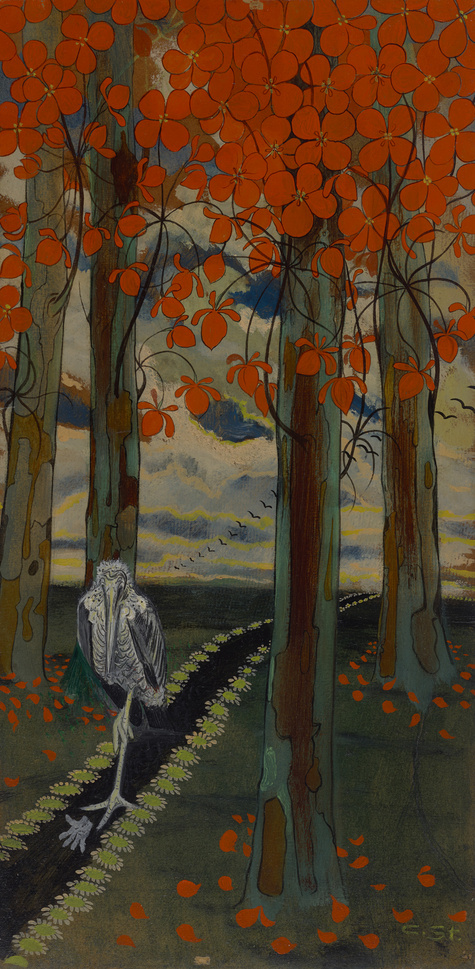

In the late nineteenth century, Munich became an early center of the international style generally known in the English-speaking world as Art Nouveau. "Jugendstil", the German name of this innovative movement of artistic renewal, which soon breathed fresh life into all domains of visual life, derives from the magazine "Jugend" (Youth), which was founded in Munich in 1896. Eminent painters, artisans, and architects such as Thomas Theodor Heine, Leo Putz, Carl Strathmann, August Endell, Hermann Obrist, and Richard Riemerschmid contributed to "Jugend". Their doyen was Franz von Stuck, who was an influential teacher at the Munich Academy for more than two decades; Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee were briefly among his students as well.

Franz von Stuck (1863 – 1928) emulated the model of Lenbach, his senior by a generation, but under more modern auspices. He created symbolist paintings, often based on motifs from mythology, that captured the spirit of the "fin de siècle" and showed affinities with the work of the Secessionists; he also socialized with dancers and actors and painted their portraits. The shift from historicism to a revival of classicism and the "Jugendstil" is evident in the magnificent residence and studio he built for himself; synthesizing the arts, the ensemble defined the image of the fashionable prince of painters in turn-of-the-century Munich. His painting "Salome" shows a femme fatale striking fear into the hearts of men. It is influenced by performances of contemporary dancers who shocked the public morals of the time with scanty dresses and explicit eroticism; they were inspired in turn by the 1904 Munich premiere of Oscar Wilde’s play "Salome".

In 1896, the same year that the journal "Jugend" was founded, the painter, graphic artist, and writer Thomas Theodor Heine and the publisher Albert Langen launched the political satire weekly "Simplicissimus". Heine's extensive estate has been at the Lenbachhaus since the 1950s.

Oskar Zwintscher, Portrait of the Artist's Wife, 1901, acquired with the support of the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung

Oskar Zwintscher, Portrait of the Artist's Wife, 1901, acquired with the support of the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung Richard Riemerschmid, In Open Nature, 1895 © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018

Richard Riemerschmid, In Open Nature, 1895 © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018 Carl Strathmann, The Paradise Tree with Snake, ca. 1900

Carl Strathmann, The Paradise Tree with Snake, ca. 1900

When Wassily Kandinsky, coming from Moscow, arrived in Munich in 1896, Franz von Lenbach was the preeminent figure on the city's arts scene; as the president of the Münchner Künstlergenossenschaft (Munich Artists' Association) and in other functions, he exerted a commanding influence until his death in 1904. The opposition to Lenbach’s predominance found expression in the establishment of the Munich Secession, which was founded in 1892 in direct response to the exhibition policies of the Künstlergenossenschaft. It was the first time that young artists in the German-speaking world made their dissociation from the larger mainstream arts scene official. The purpose of the new society was to promote an exhibition practice that would give equal consideration to art produced in Munich and the works of foreign artists solely on the basis of uniform criteria of artistic quality. The Secessionists sought to counteract the growing provincialism of the huge exhibitions held at the Glaspalast, but they did not champion a specific program of their own. Still, despite their explicit stylistic pluralism, they were united by their desire to overcome the prevailing historicism and develop a new artistic language; their art gradually coalesced around a flat and bright style. The Secession was thus instrumental to paving the way for modernism in the visual arts. The Secession set up its own gallery in 1906, endowing it with a collection intended to illustrate the history of the society and its contribution to the arts in selected works. The paintings and sculptures of the Munich Secession’s collection have been on permanent loan to the Lenbachhaus since 1976.

Max Slevogt, Danae, 1895

Max Slevogt, Danae, 1895 Lovis Corinth, The Lodge Brothers, 1898/99

Lovis Corinth, The Lodge Brothers, 1898/99 Harness Racing in Ruhleben, ca. 1920/1921, restituted to the heirs of Bruno Cassirer in 2003, subsequently legally acquired by them

Harness Racing in Ruhleben, ca. 1920/1921, restituted to the heirs of Bruno Cassirer in 2003, subsequently legally acquired by them Emilie von Hallavanya, Self Portrait, ca. 1905 (?), Detail © Emilie von Hallavanya / legal successors

Emilie von Hallavanya, Self Portrait, ca. 1905 (?), Detail © Emilie von Hallavanya / legal successors

Audioguide about works of the 19th century

Only if you agree, you allow us to load data from Soundcloud.

Selected works of artists of the 19th century