Picture Perfect

Views from the 19th Century –

The nineteenth century is the age of pictures. Visual art reached larger audiences than ever before. Artists—women and men—powerfully shaped the culture of their time, the spectrum of themes considered worthy of depiction was substantially enlarged, and "picture perfect" became the highest form of praise. The motifs that were invented then still define our ideas of romantic feeling, of sadness and beauty. Over the course of the nineteenth century, an enormously diverse universe of narrative visual art emerged whose capacity for formal innovation remains thrilling today.

"Picture Perfect" presents a reinterpretation of the Lenbachhaus’s collection of nineteenth-century art. The new display covers an unusually wide range of artistic styles and subjects in an effort to offer fresh perspectives on this rich visual culture. Complemented by photographs and film and audio samples, it charts the contemporary context in which themes and imageries originated and spotlights some of the ways in which the long nineteenth century continues to inform contemporary culture today.

In the nineteenth century, the people who visited exhibitions and collected art, who read books, journals, or travel guides expected to encounter vivid portrayals and entertaining stories, and so many artists tended to affirm existing realities rather than subject them to critical scrutiny, but we can also glimpse moments of irony that suggest an awareness that their productions were often based on models and façades. Still, the rapid growth of the imagery in public circulation meant that the world of individual experience was drastically enlarged.

In the hands of artists, natural scenes became the picture-postcard vistas we still like to take in. Traditional dresses and rural traditions were revived or, in some instances, invented out of whole cloth in the nineteenth century; some proved so compelling that people around the world now flock to Oktoberfests to perform as "Bavarians". In the German mind, the forest is central to the relationship between humans and nature, a visual and emotional space.

Painters who moved to the countryside not only interpreted the rural world, they also experimented with modern ways of life, and their art conveyed a sense of vitality unmarred by the constraints of urban decorum. As portraitists of the bourgeoisie and aristocracy, they helped define the public image of these social strata; they explored the relations between the sexes and class differences. The entire "grand theater" of the modern world waited to be cast into visual representations: phenomena as diverse as life in the historic past, the problems of the natural sciences, or the allure of spiritism.

Curated by Susanne Böller

Works

Albrecht Adam

Gebirgslandschaft mit pflügendem Bauern, 1825

Lovis Corinth

Frühstück in Max Halbes Garten, 1899

Lovis Corinth

Der Walchensee bei Mondschein, 1920

Ludwig Eibl

Jagdstillleben, 1874

Adolf Heinrich Lier

Buchenwald im Herbst, 1874

Johann Georg von Dillis

Das Lechtal mit Blick auf die Zugspitze, um 1809

Christian Ernst Bernhard Morgenstern

An der Amper bei Oberhausen, um 1840

Philipp Helmer

Maler am Waldrand, undatiert

Johann Sperl

Wiese vor Leibls Atelier in Aibling, 1893

Max Slevogt

Frau Luise Papenhagen, 1897

Hermann Baisch

Landschaft mit Viehherde, 1880

Wilhelm von Kobell

Auf der Gaisalm, 1828

Johann Friedrich Hennings

Studie vom Königssee, 1870

Franz von Defregger

Das brennende Seppenhaus in Reith, 1890

Eduard Schleich der Ältere

Oberbayrische Flußlandschaft bei Gewitter, um 1860

Thomas Theodor Heine

Der Angler, 1892

Joseph Wopfner

Hänsel und Gretel, 1875

Emilie von Hallavanya

Selbstbildnis, um 1905 (?)

Carl Rottmann

Vorgebirgslandschaft bei Murnau, vermutlich 1830er Jahre

Ludwig von Löfftz

Alte Frau in Interieur, 1871

Anton Zwengauer

Herbstmorgen, 1841

Otto Gebler

Waldinneres, undatiert

Peter Kálmán

Atelierpause, um 1940

Gotthardt Kuehl

Jagdstube, undatiert

Thomas Theodor Heine

Wirtsgarten in Dachau, 1890

Fritz Schider

Chinesischer Turm, um 1873

Thomas Theodor Heine

Teufel, vor 1904

Friedrich August von Kaulbach

Gruppe vom Münchner Künstlerfest von 1876, 1876

Jules Fehr

Franziska mit dem Reiherhut, 1915

Oskar Zwintscher

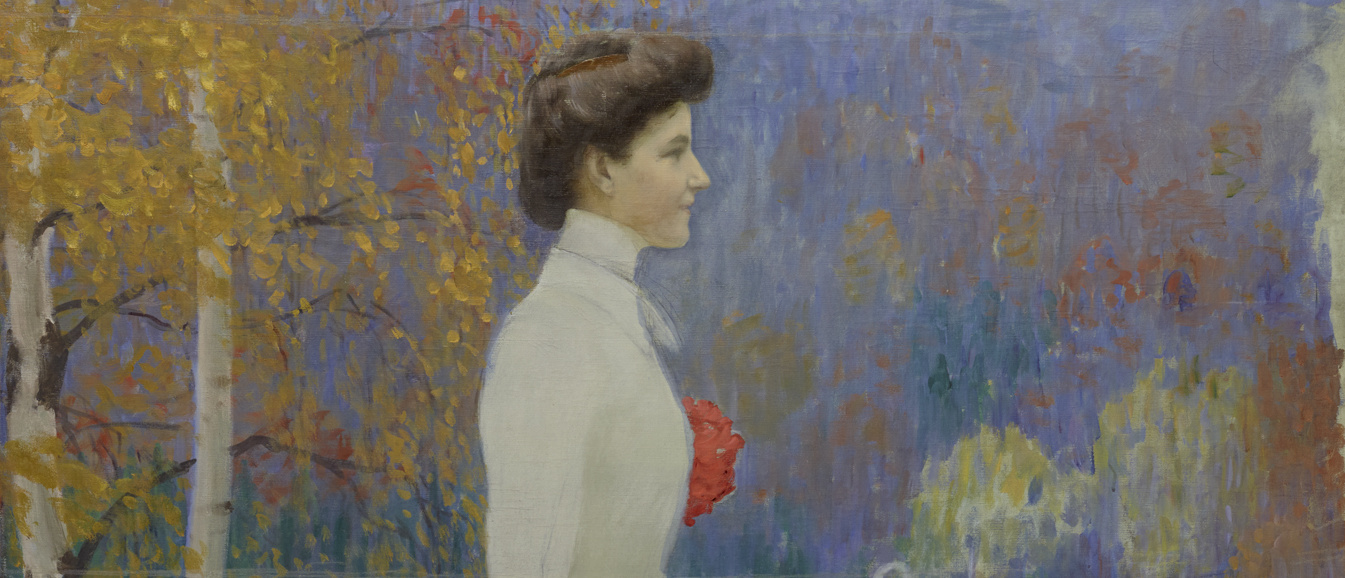

Bildnis der Frau des Künstlers, 1901

Franz von Lenbach

Luitpold Prinzregent von Bayern, 1896

Lovis Corinth

Der Pianist Conrad Ansorge, 1903

Albert von Keller

Die Auferweckung des Jairi Töchterlein, vor 1886

Albert von Keller

Die Auferweckung des Jairi Töchterlein, vor 1886

Christian Landenberger

Atelierszene, 1910

Leo Putz

Spätherbst, 1908

Albert Weisgerber

Sommertag, 1907

Eduard von Grützner

Bauerntheater, 1882

Carl Spitzweg

Ausruhende Spaziergänger, um 1865/1870

Hugo von Habermann

Weiblicher Kopf, 1875

Johann Georg von Dillis

Gebirgstal (Gegend bei Ruhpolding), um 1817

Christian Ernst Bernhard Morgenstern

Der Starnberger See, 1840er Jahre

Otto Seitz

Waldinneres mit Staffage, undatiert

Fritz Baer

Abend im Walde, um 1914

Gabriel von Max

Das Wohnhaus des Künstlers in Ammerland, nach 1875

Hugo Kotschenreiter

Nach der Jagd, 1875

Wilhelm Trübner

Brüsslerin mit blauer Krawatte, 1874

Johann Georg von Dillis

Der Hirschgarten bei München, um 1830

Wilhelm von Diez

Entwischt, 1890

Arthur Langhammer

Heimkehr von der Kirchweih, um 1895

Anna Hillermann

Selbstbildnis im Atelier, um 1900

Wilhelm von Kobell

Nach der Jagd am Bodensee, 1833

Mathias Schmid

Die Feuerb'schau, um 1888

Ludwig von Löfftz

Waldinneres, undatiert

Carl Rottmann

Vorgebirgslandschaft bei Murnau, vermutlich 1830er Jahre

Heinrich Bürkel

Auftrieb zur Alm an der Benediktenwand, 1836

Heinrich Bürkel

Der Untersberg bei Salzburg, 1863

Ludwig Gebhardt

An der Würm bei Mühltal, 1866

Arthur Georg Freiherr von Ramberg

Zwei Grisaillen zu "Hermann und Dorothea", 1865

Carl Rottmann

Hirschjagd am Hintersee bei Berchtesgaden, 1823

Lovis Corinth

Die Logenbrüder, 1898/99

Max Slevogt

Selbstbildnis mit schwarzem Hut, 1913

Wilhelm Leibl

Kopf eines Blinden, um 1866/67

Joseph Wopfner

Heuboot auf dem Chiemsee, um 1885

Hans Olde sen.

Caroline Großherzogin von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, um 1903

Gabriel von Max

Anthropologischer Unterricht, nach 1900

Franz von Lenbach

Hüterbub auf einem Grashügel, um 1859

Julius Hüther

Sonnenbad, 1911

Albert von Keller

Die Auferweckung des Jairi Töchterlein, vor 1886

Albert von Keller

Die Auferweckung des Jairi Töchterlein, vor 1886

Bruno Piglhein

Spiel im Freien, vor 1894

Fritz von Uhde

Engel im Atelier, 1910

Charlotte Berend-Corinth

Henny (Henriette Seckbach), 1905

Ferdinand Staeger

Nächtliche Musik, 1918/19

Lovis Corinth

Selbstbildnis mit Skelett, 1896